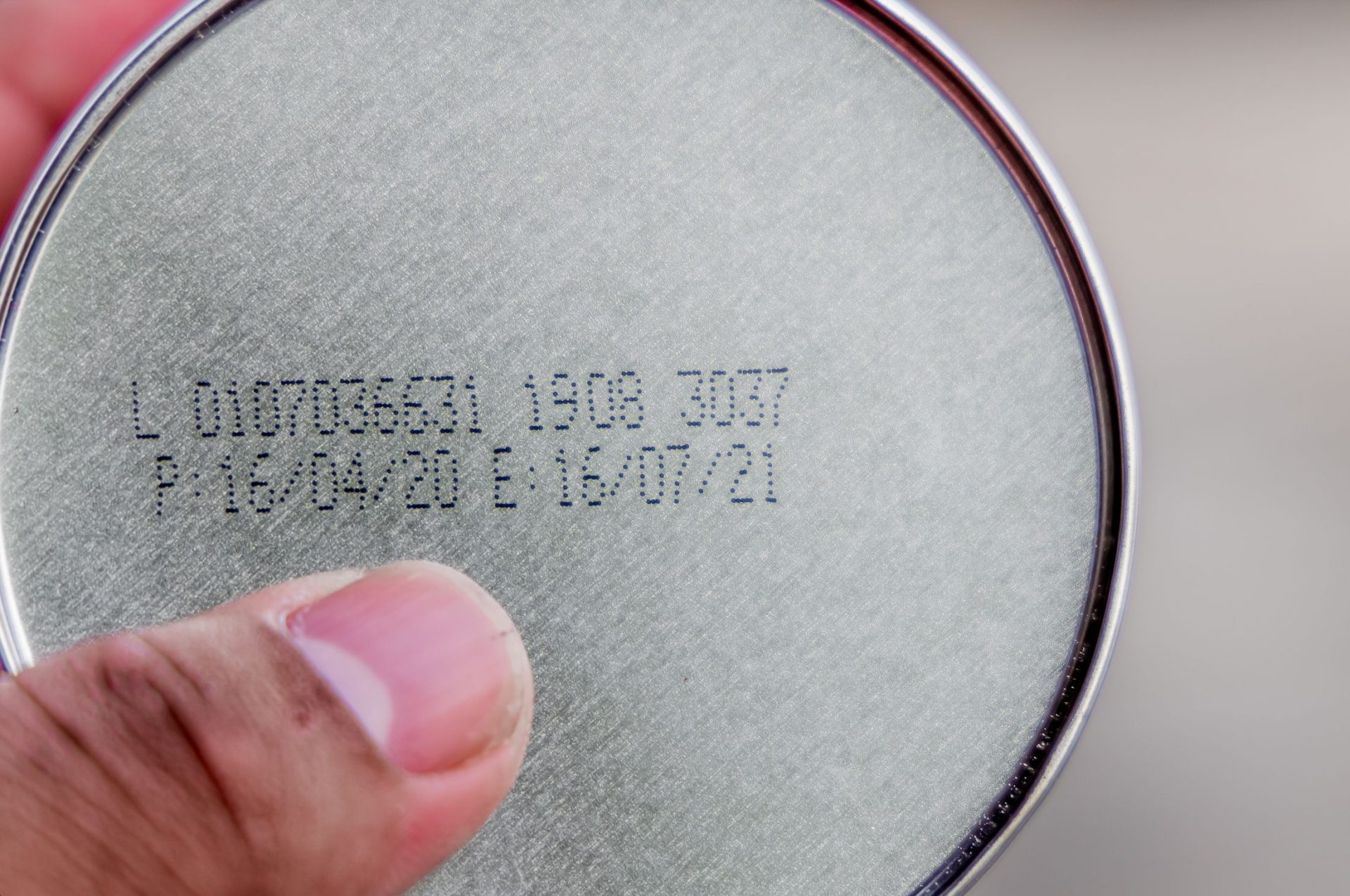

Have you ever had to squint at a packet to work out if what you want to eat is past its use by date or best before date? For some people, the two are interchangeable, and perfectly good food that has passed the date given is thrown into the bin.

In times when we know that the UK produces somewhere around 9.5 million tonnes of food waste, that’s a problem.

Could they be one of the culprits of food waste?

The history of the best before date and sell by date

If you’ve ever been in retail, you’ll have seen a sell by date, detailing the date by which the product should be sold or removed from shelf life. This does not mean that the product is unsafe to consume after the date and there is around an extra one-third of a product’s shelf-life for a consumer to enjoy the food.

The term was introduced by Marks & Spencers in the 1950s and was then launched into the stores as a “sell-by-date” in 1973. Back before this point, we were sniffers and shakers, testing and eyeballing products. In a society that is increasingly litigious, it’s worth mentioning the full respect required by a use by date. That soft cheese isn’t going to last forever. So, long live the use by dates. But what about sell by dates and best before?

Food that has reached its sell-by date cannot be sold to consumers and is often disposed of. Some of it may be salvaged for other purposes such as animal feed or bio-energy, but the majority of it ends up in landfills. Food business operators (FBO, which means any business involved in the manufacture or supply of food for human consumption, including retailers) can change the durability indication (best-before and best-before-end dates, not use-by dates) which gives them a lot of power in this area.

At present, most prepacked foods must be marked with either a use-by date or a minimum durability date (of which there are two types: ‘best before’ and ‘best before end’).

Who is wasting food – the retailers with sell by, or the consumers at best before?

The culprits behind waste are often pointed at production and retail. A study conducted by SIK in 2011 suggested that the total global food waste is around one-third of all food produced for humans, amounting to about 1.3 billion tonnes, and in all areas, the consumer impact was far lower than that of production or retail.

The fact is, we have some problems with the definitions of what food waste actually is.

Both the UN and EU’s definitions of food waste include total food – and many feel it is not right to suggest that food produced for non-human consumption such as fertilizer, biomass, or animal feed should be categorised as food waste. To some, only food that ends up in landfills should be regarded as being wasted, or preventable waste. Regardless, there are a few reasons why the buck stops with the producers and retailers.

Surplus food

Surplus food delivered outside of scope to requirements is a big issue. Many retail-farmer contracts ask the farmers to supply the required quantity targets or risk being removed as suppliers. The result? They produce more food than necessary in order to ensure that they keep their retail contracts.

Destination and location

Location is everything, and when we eat food from further afield, the chances of it making its journey looking tip-top are slim. (Ask anyone who’s been on a long-haul flight!)

The UN estimates about 6% of food loss in North America occurs because of handling. Strawberries are often highlighted as a troublesome example because after 7 days from picking, they deteriorate. Consumers want an un-bashed, ripe looking, tasty fruit served to them, regardless of the season. That leads to the next problem…

Not the right look for consumers

Beauty is only skin deep – unless you have gills. How food appears to the retailers, who are predicting in turn how it’s viewed by consumers is another big issue. Nearly 2.3 million tonnes of fish are discarded each year because they don’t look as they should, and stats suggest that a huge, saddening 40 to 60 percent of all fish caught in Europe are discarded for this reason. However, the stats suggest consumers aren’t as fussy as retailers think. In fact, Morrison’s tripled its sales in wonky veg after it released its promotion campaign. It seems there is an appetite for the less aesthetically pleasing fruit, which retailers aren’t spotting.

Are labels leading us astray?

A study from the Guardian into field and fork shows consumer waste can represent a large portion of waste overall. Keeping with strawberries, a study into US consumers showed that while 10% are wasted in-store, a further 35% are wasted at home.

Are best before labels putting us off?

At present, it’s a requirement for food to have a best before or a use date, but there are areas where it can be removed. Following on from Norway’s lead in removing best before dates from fruit and vegetables, in 2018 Tesco removed their dates from fruit and vegetables. Research before the move showed that 69% of shoppers believed scrapping “best before” dates was a good idea and 53% said it would make them keep food longer.

While this was a few years ago, not every retailer has followed suit and when the stats suggest that half of all consumers might be tempted to keep food longer perhaps this is one viable solution to bringing about greater awareness to the food selection process. Using education, our instincts, and our senses to help us ascertain if food is indeed good to use.

While “use-by” dates should be taken very seriously, perhaps a rethink on best before or sell-by dates could be overdue. Teamed with an overhaul on production requirements supply chain routes and even an overhaul as to what ‘good to eat’ looks like, it could play a significant part in addressing food waste.

Is your business determined to tackle food waste and make profitable changes from doing so? Orderly can help. Contact us today.